By Cathy Pharoah, Visiting Professor of Charity Funding, Bayes Business School

Policy makers, charities, and practitioners are increasingly recognising the important role played by wealthy people in giving to good causes of all kinds, from local community needs to national arts and science facilities.

Efforts to increase this focus, and indeed to increase giving from the wealthiest, will be a very hard ask without better evidence on what the wealthy already contribute, and the potential scale for growth. New research has indicated that we have poor understanding of giving by High Net Worth (HNW) and ultra-HNW (UHNW) individuals in the UK, and that its level and scope are being significantly under-estimated. This leaves a weak evidence base for policies that sustain and grow HNW giving.

The research concluded that this gap in our knowledge was left by existing giving surveys which do not collect data on donor wealth, seriously under-represent the very wealthy, and vary widely in features such as types of donor included, timescales, kinds of beneficiaries included and what is measured (eg tax relief, size or type of gift). The outcome is a fragmented and discontinuous picture of giving in the UK, with existing research methodologies producing only a partial view of the total picture of HNW giving, sometimes with conflicting results.

To address these gaps, and demonstrate the potential of better data on HNW giving, our study trialled a test model based on survey data in which donors were selected by their wealth level, and data was boosted to include UHNW giving. Its results suggests that total giving by the HNW and UHNW population in the UK could be worth around £7.76 billion, and possibly much more [1]. This figure is largely missing from current estimates of giving in the UK.

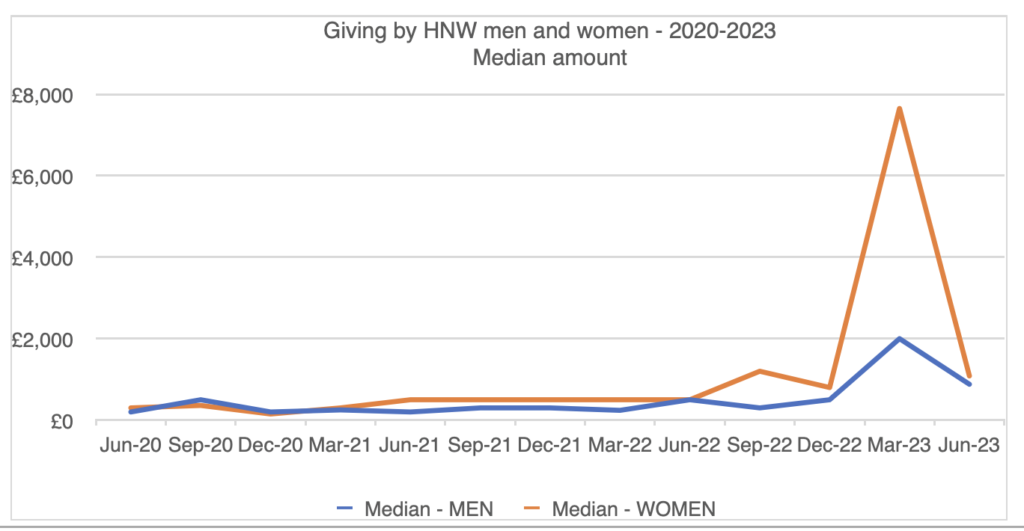

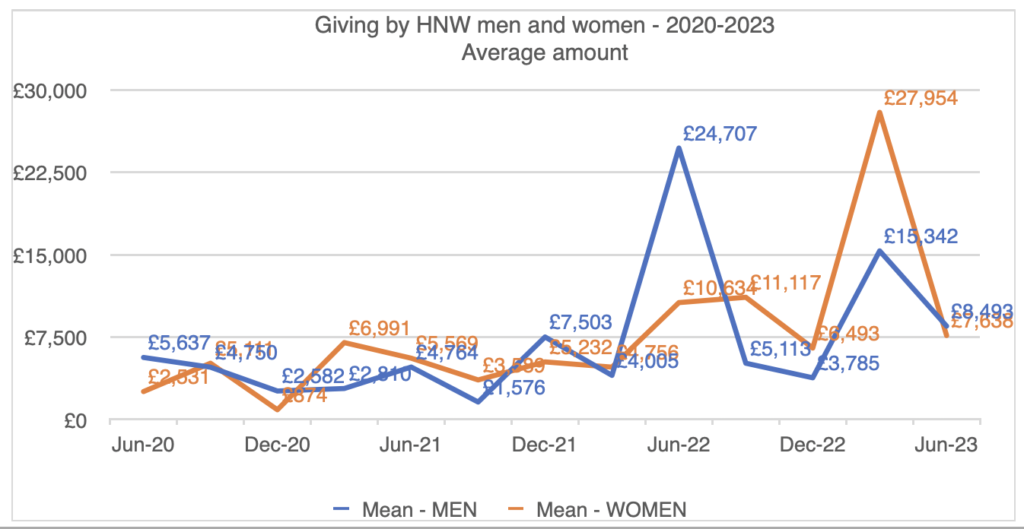

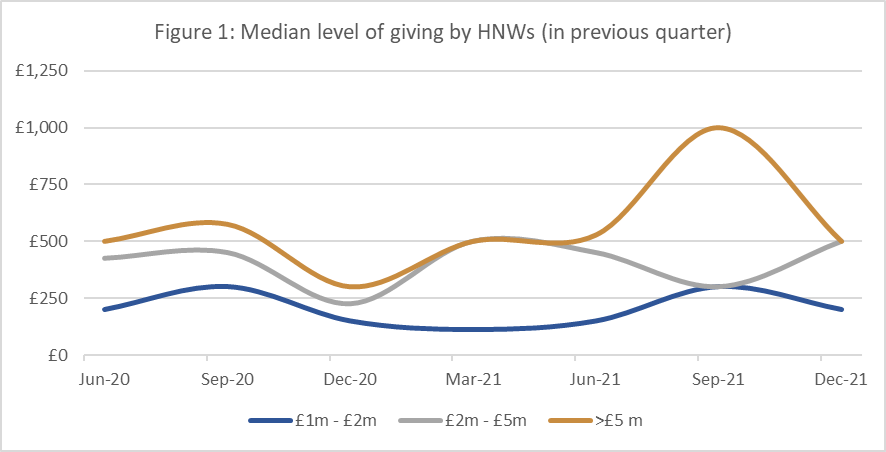

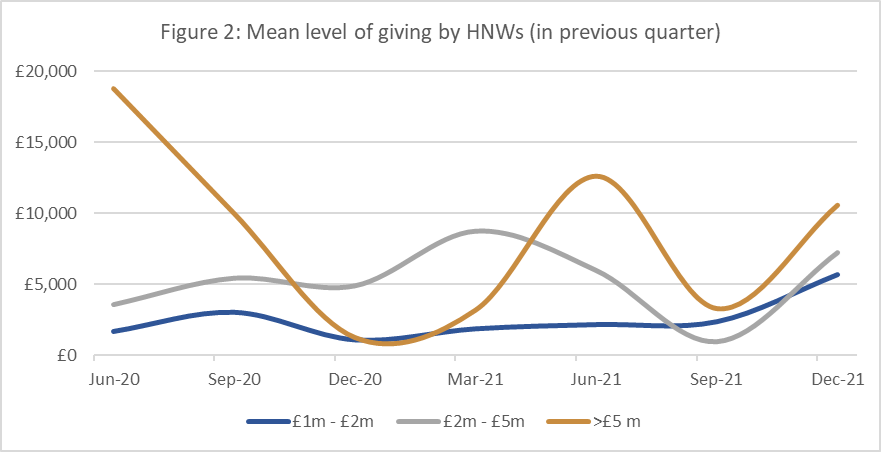

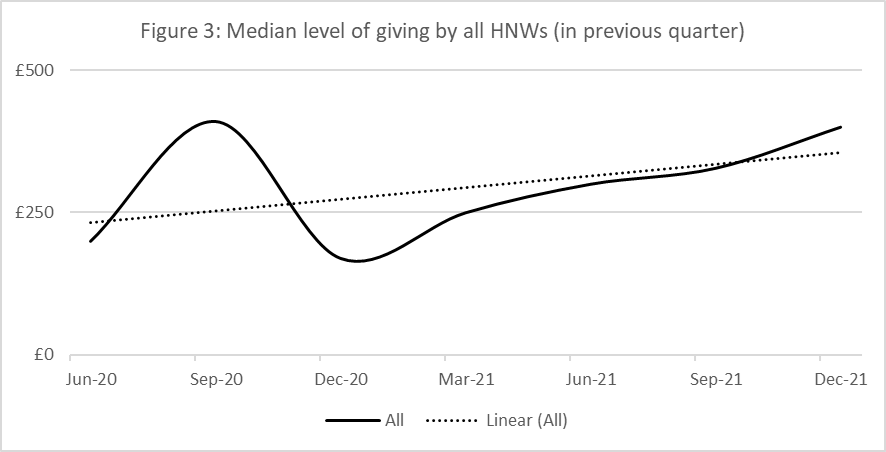

A unique data-set was compiled from pooling responses to targeted questions on the level of giving among UK millionaires in 2020, 2021, 2022 placed quarterly by Beacon Collaborative in Savanta’s MillionnaireVue survey. This quarterly survey targets 300-500 individuals with investable wealth of >£1 million (ie. excluding property). For the test model, the data was boosted with figures on UHNW giving in the Sunday Times Giving List, where the top six highest donations are worth more than 40% of total STRL giving in each year.

In addition to the new estimate of £7.76bn for HNW giving, the results of the research show a 91% participation rate in giving by people with wealth of >£1 million. And importantly, in spite of some limits to the wealth data collected in the survey, results also indicate a moderately strong relationship between investable wealth and giving.

The finding that the more wealth people have, the more they tend to give is clearly significant for strategy at fundraising and policy levels. The finding suggests many HNW and UHNW individuals are giving based on their level of wealth, not their income. In turn, this suggests it is the asset base of an individual that provides the financial security which prompts the decision and capacity to give larger amounts.

A targeted survey with more extensive wealth data could test the strength and nature of the relationship between wealth and giving, and indicate, for example, which wealth thresholds are the most significant for changes in giving decisions, and how.

In addition to better financial insights into HNW giving, a targeted survey which could provide more models of giving behaviours would be particularly useful to those targeting or supporting HNW and UHNW donors. The patterns which have been found to characterise lower level giving in the general population cannot simply be extrapolated to this very different group of donors, who are likely to be influenced by factors such as wealth advice, business and professional interests, and global trends.

Areas for further research could also include the causes and institutions they support, the effect of changes in personal circumstances on donor decision-making, the ways in which HNW give including through legacies, foundations and gift funds, involvement in social investment, the numbers of charities supported and gifts made.

Based on this review of existing data, it was concluded that a new survey was needed, whose key features would primarily include:

- inclusion of data on wealth, so that HNW giving could be studied in relation to HNW wealth

- boosting data on hard-to-access UHNWs, to ensure all giving was included in final estimates

- a sufficiently large sample of wealthy people to cover the whole wealth spectrum

- asking donors themselves directly about their giving amounts and behaviours.

Despite the huge financial and social value of the philanthropy of the UK’s wealthiest people, very little giving research has a focus on high net worth (HNW) giving. This is particularly surprising given the distinct nature of HNW philanthropy, and its specialised professional fundraising and wealth advisory approaches.

It leaves the philanthropy sector hamstrung in its ability to advocate effectively with policy makers. The lack of clarity and coherence in data significantly hampers our ability to grow and develop HNW giving. We cannot call for regulatory changes, tax incentives, strategic investment or match funds if we cannot pinpoint the size of the potential prize.

Without the data to build a clear business case fundraising organisations cannot attract investment to develop their capabilities and capacity to work with major and HNW donors. Last but not least, the data gap leaves the door open for media narratives that the rich are not pulling their weight, which we cannot challenge. This is only likely to demotivate potential donors.

The results of this new HNW philanthropy market sizing project more than demonstrate the case for investment in a better study of HNW giving.

[1] Confidence limits were calculated to range between £6.45 billion and £11.99 billion

_________________________________________________

Scoping the high net worth philanthropy market

Author(s)

Cathy Pharoah, Cath Dovey, Tom McKenzie, Vivek Thaker

Year

2023

The work was funded by Arts Council England and City Bridge Foundation

The research survey was carried out and analysed by Savanta, through questions included in their MillionaireVue omnibus survey, commissioned by Beacon Collaborative. Savanta provided access to additional economic and demographic data.

Authors

- Cathy Pharoah is a Visiting Professor of Charity Funding, Bayes Business School

- Cath Dovey is Co-Founder, Beacon Collaborative

- Tom McKenzie is Professor of Economics, CBS International Business School

- Vivek Thaker is Associate Director, Savanta