On 29 February, The Beacon Collaborative hosted the fourth Beacon Philanthropy & Impact Forum at the Guildhall in London. The invite-only event brought together 251 participants from across the philanthropy and impact communities and included philanthropists, impact investors, sector leaders, charity leaders, policy makers, academics, think tanks, regulators and media.

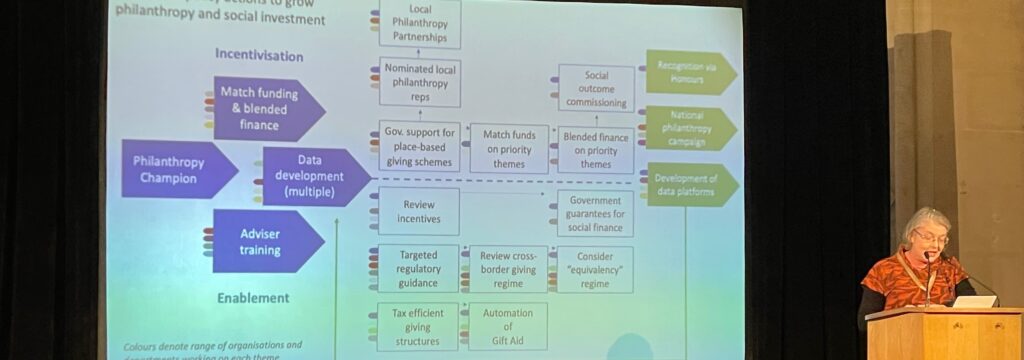

The purpose of the day was to bring together cross-disciplinary expertise to answer the question: What will it take to grow giving and impact in the UK?

During the day, attendees heard presentations and panel discussions from:

- The Rt Hon Stuart Andrew MP — Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Sport, Gambling and Civil Society

- Thangam Debbonaire MP — Shadow Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport in the United Kingdom

- Sacha Sadan — Director of ESG at the Financial Conduct Authority

- Rory Brooks CBE — Philanthropist and trustee at The Charity Commission

- James Broderick — Chair of the Impact Investing Institute

- Ajaz Ahmed — Philanthropist, Ajaz.org

- Patricia Hamzahee — Advisor, impact investor and philanthropist

- Zaki Cooper — Founder of Integra Group

- Jeremy Rogers — Manager of the Schroder BSC Social Impact Trust and Chief Investment Officer at Big Society Capital

- Giles Shilson — Chair of City Bridge Foundation

- Cath Dovey CBE — Co-founder of The Beacon Collaborative

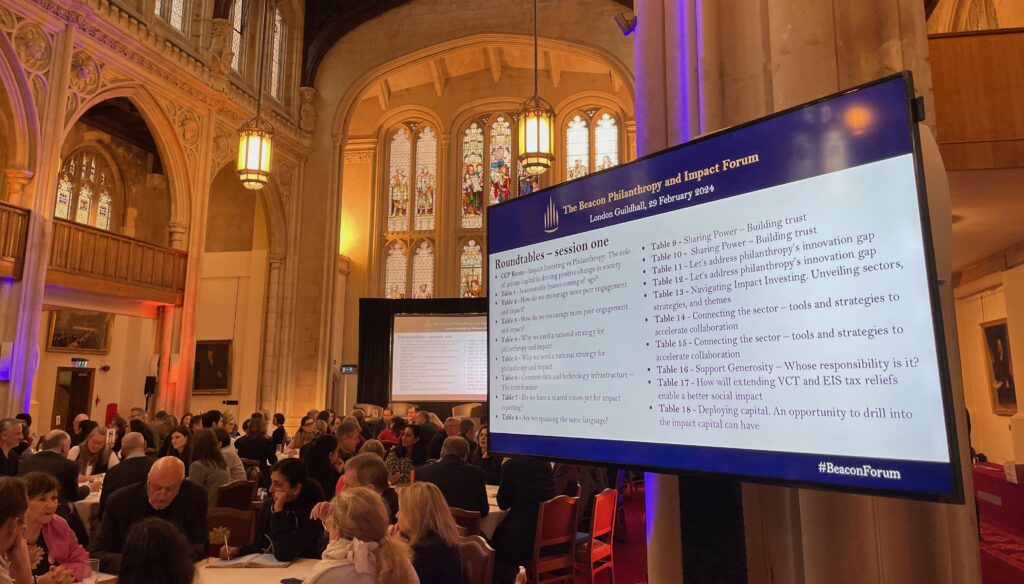

Participants also took part in 60 lively roundtable discussions during which they swapped experiences, insights and wisdom as they tried to examine how we can break down the silos between the impact community and financial community.

Key themes captured

During the roundtables, the points of discussion were captured and the key findings extracted and formulated into the following themes:

- Nurturing and supporting generosity and social impact requires long-term investment and would benefit from a national strategy for philanthropy

- We need to continue building tools to support personalised philanthropy strategies

- Sustainable investment strategies are moving from ESG towards impact investment, but more will be needed from policy makers and regulators

The challenge of effective impact measurement is nuanced with different needs and motivations in the philanthropy and impact investment sectors.

Each of these themes have been expanded and can be found in the Beacon Forum summary document.

The document summarises the themes that emerged from our keynote speakers and panel discussions and includes comprehensive notes, insights, quotes and questions collated from the roundtable discussions.

As a summary of key current issues, we hope it will be helpful to inform your ongoing work.

Download the Forum summary document

Perspectives and input were so valuable

This year’s Forum was an inspiring day that saw a rich exchange of ideas, dynamic discussions, valuable networking and potential future collaborations from experienced leaders from across the impact community.

We would like to thank all participants for their insightful contributions and range of perspectives and ideas. These will be valuable as we continue working towards advancing the philanthropy and impact agenda.

Thank you

The Forum could not have happened without our volunteer facilitators, note-takers and our wonderfully generous sponsors, supporters and partners:

- Schroders

- Barclays Private Bank

- Redington

- City Bridge Foundation

- Charities Aid Foundation

- Owen James Events