Seven cycles of pulse surveying among high-net-worth individuals in the UK, from the height of the pandemic until now, suggest regular giving is increasing among those with higher levels of investable wealth. The results also highlight the need for improved monitoring of giving patterns among the asset rich if we want to sustain growth momentum.

Our latest quarterly survey results – covering the period September to December 2021 – show the effects of the pandemic are receding on giving patterns, revealing underlying trends in recent UK philanthropy.

The run-up to Christmas 2021 saw an uptick in the number of big gifts by wealthy individuals. With an increase in the average level of giving in all wealth bands, the results suggest growth in seasonal giving was closer to pre-pandemic levels.

The average level of giving jumped to £6,400 in the three months to December, with more than 25% saying they gave more than they had planned.

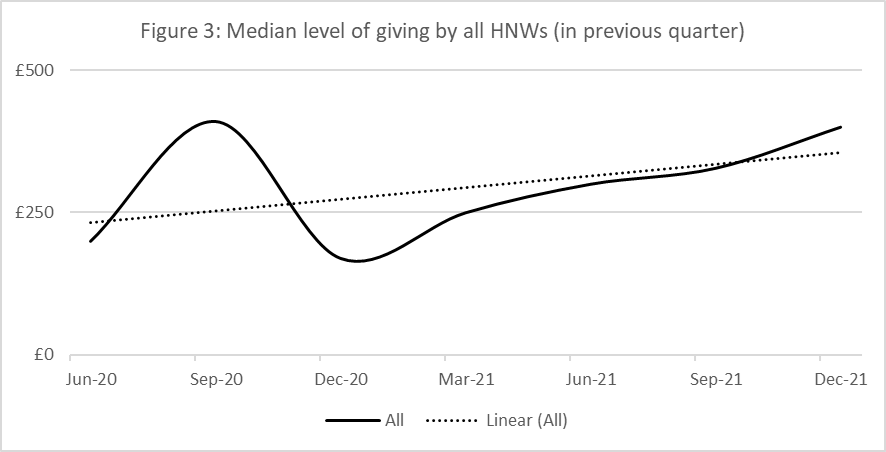

The median level of giving has also continued on a steady upward trend, reaching £400. The last time the median was at this level was in September 2020 as the pandemic peaked in the UK.

These results come from the Beacon Collaborative’s quarterly pulse survey of high-net-worth giving trends, conducted in partnership with Savanta. The December results are based on survey responses from 514 high-net-worth individuals in the UK[1].

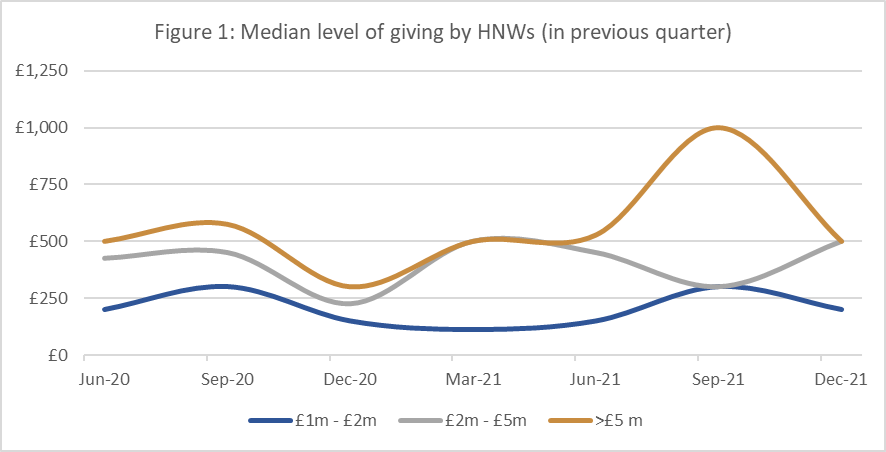

Figure 1: Median level of giving by HNW individuals from June 2020 to December 2021.

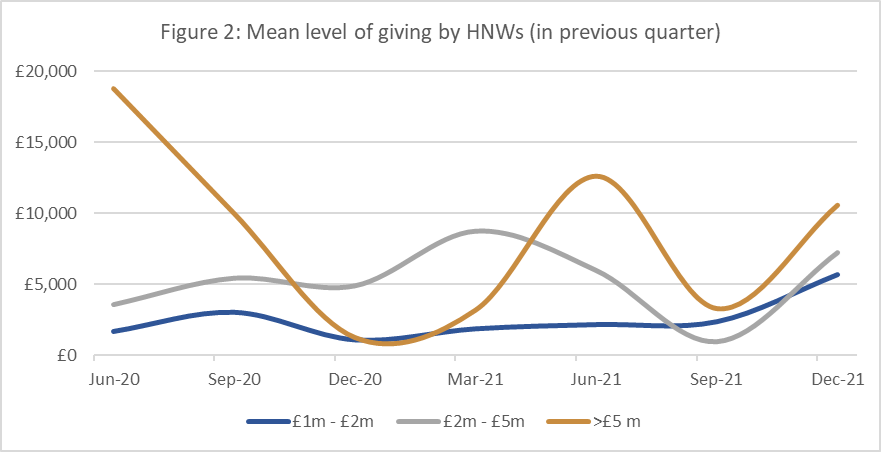

Figure 2: Mean level of giving by HNW individuals from June 2020 to December 2021.

Growing evidence that more wealthy people are starting to give more, more often

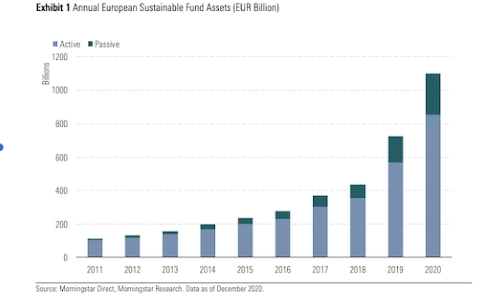

While sporadic big gifts are a consistent feature in philanthropy, and are actively sought by most philanthropy fundraisers, it is the gentle increase in the median giving level that offers significant potential. Since June 2020, the survey results suggest compound quarterly growth of around 12% in the median level of giving, from £200 to £400.

Figure 3: Median level of giving by all HNW individuals from June 2020 to December 2021.

While the quarterly level of giving is still proportionately low in the high-net-worth population, at £400 in December 2021, the median trend suggests more wealthy people have been giving more often at higher levels each quarter since June 2020. This bodes well for engaging more wealthy individuals on their philanthropic journey.

Propensity to give is linked to asset levels (not income)

We began this quarterly analysis at the start of the Covid crisis in order to open a window on the giving trends among high-net-worth donors.

Over this period, a number of distinct patterns are emerging, most notably that those with higher asset-levels do give more – not a lot more, but there is a higher propensity to give major gifts and larger regular gifts.

The consistent upward trend in the median giving level is also noteworthy, particularly as recent analysis from Pro Bono Economics has shown giving levels decreased among top earners between 2011 and 2019.

Mind the Giving Gap uses HMRC income and tax data and determines that those with a median income in the top 1% of earners saw their earnings rise from £247,000 to £271,000 during this period. During the same period, their typical donation fell 20% to £48 per month.

The detailed analysis contained within the report underscores multiple worrying trends that have characterised British giving across the wider population since the financial crisis of 2008, resulting in lower participation rates and lower levels of giving. It also makes a number of valuable suggestions for changing the dynamics of philanthropy in the UK.

The analysis by Pro Bono Economics is thorough and comprehensive, but it is important to note that the conclusions on high-net-worth giving rely on income data and donations reported in self-assessment forms. This represents only a segment of the wealthy population.

The high-earner category includes a sizeable population in the UK that is typically referred to as “cash-rich and asset-poor” by the wealth management community. This means they have high incomes, but their income funds their daily life expenditure and they do not have the extensive savings and investments that provide financial security.

As we can see in Figure 1 and Figure 2, those with lower asset levels typically display a lower median giving level and give fewer large gifts. Among the asset-rich, the dynamics are more positive.

Pro Bono Economics’ analysis will miss significant segments of UK’s asset-rich population, such as those on low or moderate incomes who draw down from investments what is needed for their daily life needs.

Our analysis suggests that an increasing number of individuals in this population are giving more, more regularly. If we want to encourage this trend, then it is imperative that we encourage philanthropy to be seen as a normal part of a “wealthy lifestyle” in the UK, so that income is drawn down to cover their annual gifting goals.

It will also have captured only a proportion of amounts given by wealthy individuals from giving structures, such as donor-advised funds or philanthropic family trusts. These vehicles typically receive infrequent large lump sums that are then gifted out over a period of time.

Key lessons from emerging data on high-net-worth giving patterns

There are a number of key lessons we can draw from these two separate analyses.

- Firstly, understanding how much is given philanthropically, and by whom, is a complex challenge requiring multiple data sets that are not easily available.

- Secondly, if the asset-rich population shows the highest propensity to give in larger amounts, this population merits greater study for their philanthropic activity.

- Thirdly, regular high-net-worth giving, measured by the median, should be monitored as a significant indicator of philanthropic growth. This indicator is more helpful to understand what is happening in the wider wealthy population than tracking one-off big gifts or monitoring the mean (average), which fluctuates significantly in response to sporadic major gifts made by a tiny fraction of any sample group.

If we want to understand the contribution to civil society of the wealthy population, we need to understand how median giving varies across different wealth bands, measured according to their investable assets.

It is only with this insight, measured consistently over time, that the fundraising community and the philanthropic sector will be able to establish and monitor the success of their growth strategies among those with the potential to become significant long-term supporters.

Until we have a baseline, we simply will not be able to assess “what works?” when it comes to growing UK philanthropy.

[1] Given the size of the UK wealthy population the confidence interval in the data is 4%, with a 95% confidence level. This means we can have a good level of confidence that the median figure is accurately within a tight range around £400. Sample sizes for previous quarters have varied from 303 – 514 individuals.

A note on the median and mean

* The median provides an indicator for what is happening to giving across the whole of the wealthy population. The median refers to the exact midpoint of the dataset, with half of respondents giving above this level and half below.

** The mean is sensitive to levels of giving among the most generous in the wealthy population. This is the average as calculated by adding all datapoints together and dividing by the number of datapoints in the set. It can easily be skewed by a small number of very high-level donors.