Philanthropy Is About More Than Giving: People Must Work To Change The Foundations

This article was written by Mike Schiemer – Find the original here – Republished for Beacon Collaborative with author’s permission.

The best people know when to give to those who need it and lift others up in times of need. However, philanthropy doesn’t work only through generous acts. It must provide real and long-lasting change that makes the world better. These lessons are what true philanthropists like Donald Friese and many others know intuitively.

PHILANTHROPY IS MORE THAN GIVING

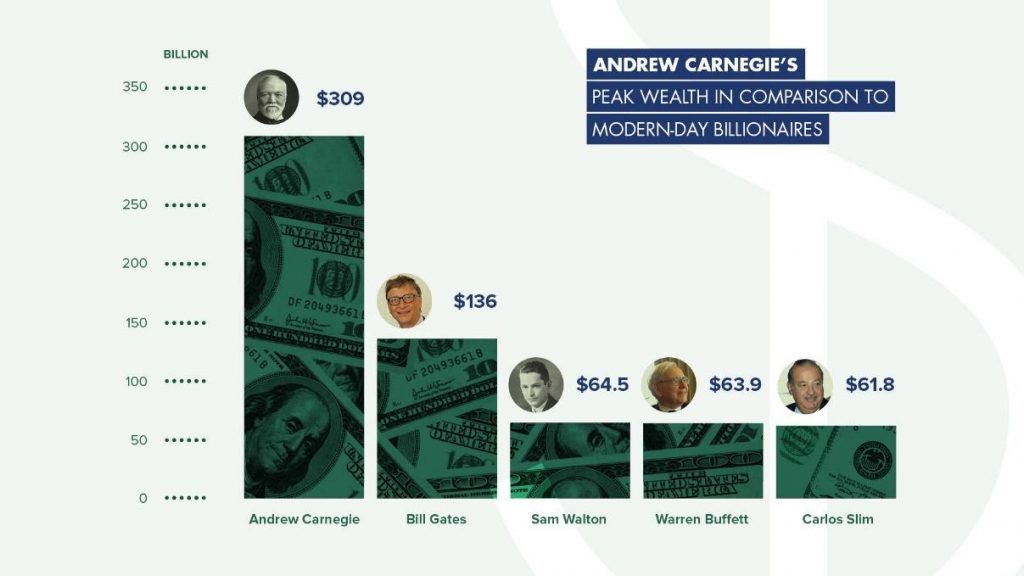

Those who think philanthropy is measured by dollar amounts often don’t understand the true nature of this process. Philanthropy needs to be transformative and restorative. It must bring something new to the life of those experiencing it and give them new hope and a better lease on life. It doesn’t just give somebody a meal for a day but strives to make it easier for them to eat for the rest of their lives.

Beyond that, it should try to change things at its core level to make the world a better place. True philanthropists look to shake expectations and help people understand suffering. Universal empathy drives true philanthropists and makes them driven to succeed in many unexpected ways, particularly for those who want to improve their community and their nation.

But how can the average person ever reach these lofty levels of expectation? It may seem unfair to expect most people to have that drive and that energy. However, those who truly care about philanthropy do have those drives and do what they can to help change the world and make it stronger. Here are a few different ways you can achieve this goal, beyond writing a cheque to your favourite charity.

HOW TO GIVE WHERE IT MATTERS

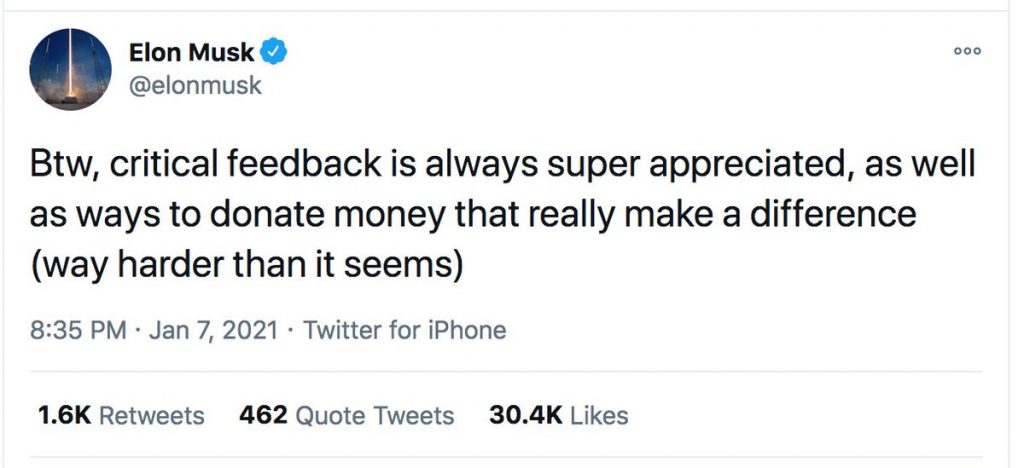

Thriving as a philanthropist requires a deep understanding of what causes matter to you and taking time to focus on them. Too many people don’t take the time to follow these steps and end up struggling to make things better. Donating money is nice but just isn’t enough for this situation.

As a result, it is important to understand many factors before you try becoming a philanthropist. Remember – you need to be willing to work hard and have a true vision about how you want to change the world. Take these steps, and things should go easier for you:

- Know What Matters to You – Have you spent the time figuring out what causes are important to you? If not, you need to think long and hard about what matters to you as a person. We all have beliefs, and your philanthropic goals should always align with them for a better chance of success.

- Find Foundations With Real Experience – Try to give to groups that work to lift people and transform their lives and the power that surrounds them. Those groups focused on real change and sacrifice are the best options for those who want their philanthropy to truly matter.

- Give Your Time and Energy – Simply donating money to a foundation is rarely enough for a true philanthropist. Most will also spend time in the trenches, working in difficult situations, teaching people how to take care of themselves, and endlessly working to better things.

- Champion the Best Causes – The world is struggling, and it is only possible to change things at their core by starting at the bottom. Champion those causes that you feel have the best chance of reaching this goal, and you can transform so many lives for the better with ease.

If you ever feel like your efforts are not enough or are not satisfying your needs, it is time to reconsider your approach to helping others in need. Philanthropy shouldn’t just be donating the same money to the same groups without thought. You need to be constantly upgrading your approach to make it more effective.

FINDING GREAT PHILANTHROPIC GOALS

Anyone interested in philanthropy needs to spend time researching the options that make the most sense for them. By seeking out those foundations and giving opportunities that truly change the world, it is possible to truly help those in need. It is best to listen to your heart in this situation. Taking into account how you feel and what feels normal and moral will make this process simpler for you. This will all help you in your journey of first-rate philanthropic deeds. It will feel great to give back!

Impatience Earth

Impatience Earth