Savanta and the Beacon Collaborative carried out qualitative research with millennial wealth creators around England, Scotland and Wales who are already giving some money, but with the right motivating tools could give more now, or in the future. These are the voices of our #YoungGivers.

It’s something that just resonates with my heart. London

Just being able to help and raise funds, and know that your money’s going to a good cause and you’re making a difference to people’s lives, makes you feel better about life and less guilty when you’re enjoying your own life. South West

I feel as well that with small charities, the work they do tends to be a bit more targeted and it’s easier to follow up on your donation, to see exactly where it’s gone and what they are doing. London

The overall research showed that this generation are, at heart, generous and want to do more. They understand how lucky they are to be in their situation but sometimes the other, seemingly more immediate, pressures of life have to take priority and giving takes a back seat. However, when challenged to think about giving they are engaged and thoughtful, wanting to know more and make plans that fit into their lifestyle and longer-term family plans.

I think having to think about why you do what you do or what you get from it was quite tricky, I think we all do it to get the satisfaction that you’ve done something good but probably don’t think of it that way unless asked to look deeply. North

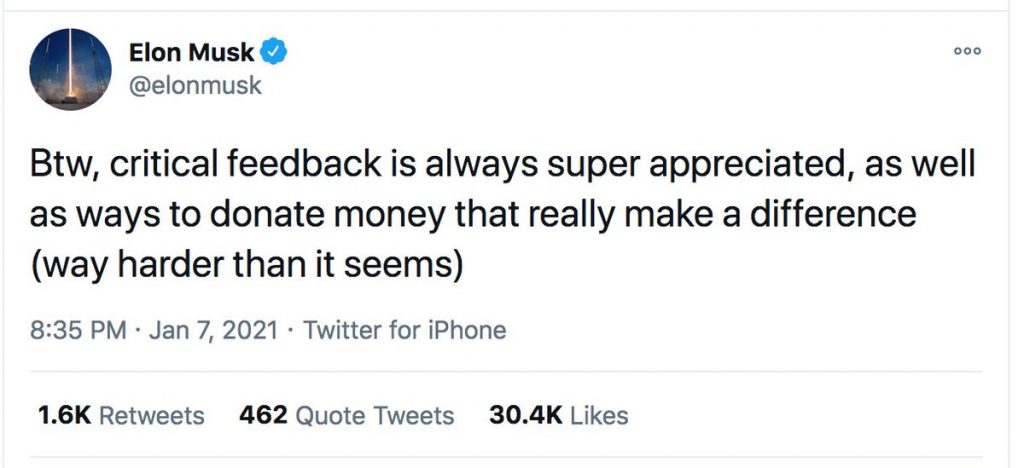

So, what can be done to fit giving into the routine of busy lives, or to motivate these young wealth creators to do more?

In a world dominated by easy access information and short sound bites, charitable organisations can streamline their communications to be front and centre of a potential giver’s thoughts.

We found that charity is thought of as local and personal. Some charitable activities, notably the arts and advocacy, are not really thought of as charitable when a young wealth creator is making a donation decision. Sometimes it’s personal as they know someone who has been through a trauma or had a disease. Sometimes there’s a “there but for the grace go I” empathy. Charities not on the radar of givers need to do more to show that they are charitable and how they directly impact lives.

However, there is a sense of fatigue at the number of sponsored events that happen, especially in large workplaces and the feeling that then charity is done. There is also a need to know where the donation will go and that it will be useful, therefore charities that appear wasteful are rejected.

The go-to charities have solid reputations and easy-to-understand messaging. They produce images and stories that resonate on a personal level. They show the outputs of their work in smiling faces and stories of named people. They show the direct impact of a donation to a person or activity that the donor can visualise easily. They provide tech enabled giving solutions that allow forgive-and-forget giving but that can be the start of regular giving over a long time period.

As yet these busy young people have not had time to fit giving decisions and planning into their lives. They do think carefully about their environmental impact and the social justice in their surroundings, but it is not associated with “charity” but behaviour and is not part of considering a holistic lifestyle. However, when their thoughts are provoked, they have the desire to contribute more, on their terms.

Successful interventions fit into their lifestyle and are relevant to professionals on a career path.

So how can charities engage better?

Our participants responded well to…

- Localised stories where people were humanised, with names and faces

- Clear objectives and the way that a donation or act creates change with suggested amounts and what that would achieve

- Tech enabled (text message, direct debit sign up) but not complex methods to give

- Suggested support beyond the financial – items that people really need that can be donated

- Something that they can be proud of even if they don’t speak about it

I’m grateful that I’m not in a position that I’ll need to use any of the charities that I donate to or any of the causes. North

When you’re under real pressure, you don’t think, ‘What I’m going to add to my really busy day is, that I need to do something for charity today.’ It’s usually when you find a gap in your schedule. South East

I think it would be good for potentially some charities to showcase and highlight ways that people could help them as well, rather than it potentially just being all money. Scotland

What can charities and their fundraisers do to engage?

- Help them understand the system – what fundraising is, why capacity building is necessary, how charity structure works

- Attributing funding to direct actions to direct impact on individuals

- Celebrate individual contributions

- Utilise skills and explain the value of them

- Make it part of a greater plan, for the donor and the charity

- Use language that is not NGO tech speak but ordinary every day terms that people understand

- Help make it part of everyday life – fit giving in with all the other activities

I’ve always wondered how people can help a charity through connections and expertise, but the amount of time, it’s almost like another job. Scotland

You’d feel a bit rewarded, at least you feel a little bit good. London

At the end of the year, I tend to make a bigger contribution from my own personal money. …..We tend to get a bonus at the end of the year and I really see that as money that I wouldn’t expect to get if I worked for anyone else, so I use a proportion of that, basically, to fund a few charities of my liking. South West

I had an example of researching a charity, and looked to see from the accounts what the director’s pay was like, and they weren’t all paying themselves a fortune…Looking to see that as much of the money as possible can go to the cause that you’re interested to support. I think it also gives you a feel of the ethos of the charity, you know, are they there for themselves? South East

What do they want to do and hear?

Views are formed by own experience, use that to harness people’s engagement, both personal and professional: people are much more sympathetic when they see something organically by going through life and have sympathy and anger for the root causes of the issues

They are happy to talk about it if they were part of a team that helped, repeating a story they have heard but less so if they are “just” donors. So, give them stories that they can remember and tell, and give them pride in their contributions.

Bring together peer donors who don’t know each other – mini giving circles to talk together about doing more and guide the discussion

Be honest about failures as well as successes. If there’s too much hype it becomes unbelievable

Volunteering is seen as a much bigger deal, more serious and a bigger sacrifice than giving money – more thought goes into it. Make volunteering easy, match it to a financial value, match the person to the commitment, then make sure they have stories to tell about volunteering. Make volunteering a qualification that can be used on a CV, something that can be using professional skills, harness skills that have a value to the charity.

For the long-term future:

Established giving is not aspirational for most people, it’s “almost like another job”.

- Help them to think of giving as an integral part of their financial planning

- Provide online tools to calculate what can be given when

- Make birthday and Christmas gifts more enticing to be done through charities or as donations on others’ behalf

- Encourage intergenerational conversations about giving and charity

- Show how much effect long term engagement/multiyear pledges can make to planning and future security

And I think it’s about having that discussion with a financial advisor to say ‘Maybe you can get a return on this, but this is done in a charitable way’, versus, ‘Why don’t you just donate this amount? And, actually, you can offset that against your tax, and this is how you would do it’. So, it’s just putting it in a bit more of a structured way. South East

The time is now. These young wealth earners are intelligent and thoughtful, conscious of the issues that surround them but need to be engaged more to enable wider understanding of the interplay between social issues and behaviours and the impact that can be had when acting in a holistic way. With targeted communications now there is the potential for these young wealth earners to be engaged major donors of the future.

I thought it was a real thought provoking session…..it’s made me want to look into giving and volunteering more than I do. Southwest

I was going to say actually after this past hour or so I don’t think I am doing enough, I think I could give more. Scotland

Impatience Earth

Impatience Earth